Mozart’s Requiem: The Unfinished K. 626 That Still Haunts Us

Alright, gather ’round, folks. We’re about to talk about something truly special, something that transcends mere notes on a page and dives deep into the human soul: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem in D Minor, K. 626. Now, I know what some of you might be thinking, “Oh, another classical music lecture.” But trust me, this isn’t just a lecture; it’s a journey into one of history’s most poignant musical mysteries, a masterpiece born from the shadows and forever imbued with an almost supernatural aura.

Imagine, if you will, a genius—a titan of composition—racing against time, literally, to complete what would be his final opus. A work commissioned under cloak and dagger, shrouded in secrecy, and ultimately left unfinished. It’s the stuff of legends, isn’t it? And in the case of Mozart’s Requiem, the legend is as compelling as the music itself.

I’ve spent countless hours with this piece, both as a listener and, at times, trying to wrap my head around its sheer complexity and emotional depth. And every single time, it strikes me anew: the power, the raw grief, the moments of serene beauty, and the profound sense of a final farewell. It’s a piece that doesn’t just ask you to listen; it demands that you feel.

So, let’s pull back the curtain on this magnificent, melancholic, and utterly unforgettable work. Let’s explore why K. 626 continues to captivate, challenge, and move us to our very core, even centuries after its creation. Get ready, because we’re diving deep into the heart of a musical enigma.

—

Table of Contents

—

The Whispers of Death: A Commission Shrouded in Mystery

To truly appreciate Mozart’s Requiem, you have to understand the circumstances of its birth. It’s not just a composition; it’s a deathbed confession, a final plea, a whispered prayer set to music. And the story behind its commission? Oh, it’s straight out of a gothic novel.

It was the summer of 1791. Mozart, then only 35 years old, was already feeling the encroaching tendrils of illness. He was working on a flurry of projects, including The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito, both triumphs in their own right. But then, a mysterious stranger appeared at his door.

This wasn’t just any stranger. This was a man cloaked in gray, a messenger from an anonymous patron, requesting a Requiem Mass. The terms were specific: Mozart was to compose it in secret, without trying to discover the identity of the commissioner. The payment was generous, but the conditions were chillingly precise.

Now, if that doesn’t sound like a plot device, I don’t know what does! This mysterious figure was, in fact, Anton Leitgeb, the steward of Count Franz von Walsegg, who wanted the Requiem to pass it off as his own composition to commemorate his recently deceased wife. A bit of a scoundrel, perhaps, but his deception inadvertently led to one of music history’s greatest works.

Mozart, already prone to bouts of melancholy and often battling financial woes, became deeply fixated on this commission. He reportedly began to believe that he was composing the Requiem for his own funeral. Whether this was a morbid premonition or a symptom of his declining health, we can’t be sure. But it certainly adds a layer of tragic irony to the entire narrative.

Imagine the scene: Mozart, increasingly frail, sketching out themes, wrestling with complex counterpoint, all while the specter of his own mortality loomed large. He saw the gray messenger as a harbinger of death, an almost supernatural figure demanding this final act of creation. It’s a heavy thought, isn’t it? To be working on your own epitaph, note by agonizing note.

This sense of urgency, of a race against an unseen clock, permeates every measure of the Requiem. You can almost hear the frantic scribbling of his quill, the deep sighs, the moments of intense focus interspersed with coughing fits. It’s not just music; it’s a dying man’s final testament, etched in sound.

And that, my friends, is where the true power of K. 626 begins. It’s not just about the notes; it’s about the agonizing human story behind them. It’s about a genius staring death in the face and, with his last breath, gifting us something eternal.

—

An Unfinished Masterpiece: Mozart’s Race Against Time

The story of the Requiem’s completion, or rather, its incompletion, is as legendary as its origins. Mozart was working feverishly on the piece throughout the autumn of 1791, even during his last illness. He was literally dictating parts of it from his deathbed. Can you even begin to fathom that level of dedication? It’s mind-boggling.

He managed to complete the Introit and Kyrie in full, orchestrated and ready for performance. The subsequent movements – the Sequence (Dies Irae, Tuba Mirum, Rex Tremendae, Recordare, Confutatis, Lacrimosa) and the Offertorium (Domine Jesu, Hostias) – were sketched out, some more completely than others. The vocal lines were largely done, the bass lines often present, but the inner voices and, crucially, much of the orchestration, remained incomplete.

The “Lacrimosa” is perhaps the most famous example of this unfinished state. Mozart only completed the first eight measures. Just eight! Imagine the heartbreak, the frustration, the sheer tragedy of a composer pouring his heart and soul into a piece, knowing it was his swan song, and then simply running out of time. It’s like reading a gripping novel only to find the author passed away mid-sentence on the final chapter.

His health deteriorated rapidly in November. By December 5, 1791, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was gone. The Requiem, his final work, was left a poignant testament to both his genius and the cruel hand of fate.

His wife, Constanze, found herself in a precarious position. She had already received half the payment for the Requiem. To get the rest, and to ensure her financial security, she needed the work completed. This is where the story takes another fascinating turn, demonstrating not only her pragmatism but also the immense respect Mozart’s students had for their master.

—

The Completions That Defined It: Süssmayr and Beyond

So, what happens when a masterpiece is left dangling? You get some very talented, albeit sometimes controversial, individuals stepping in to finish the job. For the Requiem, the primary figure was Franz Xaver Süssmayr, one of Mozart’s pupils.

Constanze first approached Joseph Eybler, another student, who began working on the orchestration of the Sequence. However, for reasons unknown – perhaps he found the task too daunting, or perhaps he was simply too busy – he eventually handed the manuscript back to Constanze.

That’s when Süssmayr stepped up. Now, Süssmayr gets a lot of flak. And, to be fair, his completion isn’t perfect. It lacks some of Mozart’s inimitable sparkle, his effortless genius in orchestration. But here’s the thing: he did it. He took fragments, sketches, and notes, and, working under immense pressure and with deep reverence for his teacher, brought the Requiem to a performable state.

Süssmayr completed the orchestration of the movements Mozart had sketched (the Sequence and Offertorium). For the final two movements, the Sanctus and Agnus Dei, there were no sketches from Mozart. Süssmayr composed these entirely on his own, likely based on themes and stylistic elements he remembered from his lessons with Mozart. He also composed the “Lux Aeterna” and “Cum sanctis tuis,” which recall the opening “Introit” and “Kyrie,” thus providing a sense of cyclical completeness.

The debate over Süssmayr’s contribution has raged for centuries. Was it good enough? Did he capture Mozart’s true intent? Would Mozart have done it differently? Of course, he would have! He was Mozart, for crying out loud. But without Süssmayr, the Requiem as we know it, the one that has moved millions, simply wouldn’t exist.

Think of it like this: you’re trying to piece together a magnificent, intricate mosaic, but the master artisan died before he could lay the final few thousand tiles. Someone else, perhaps not as gifted but still highly skilled, steps in to finish it. It might not be exactly as the master intended, but it’s still a breathtaking work, and crucially, it allows the world to see the full picture, even if some parts are approximations.

Since Süssmayr’s completion, many other scholars and composers have tried their hand at creating more “authentic” versions of the Requiem. Franz Beyer, Richard Maunder, and Robert Levin are just a few who have attempted to re-orchestrate or re-compose sections based on modern scholarship and a deeper understanding of Mozart’s style. Each version offers a slightly different perspective, a new shade to the familiar portrait.

But despite these efforts, Süssmayr’s completion remains the most widely performed and recognized. It’s the version that entered the canon, the one that shaped our collective understanding of this monumental work. And for that, we owe him a debt of gratitude, even if it’s sometimes a grudging one.

It’s a testament to Mozart’s genius that even an unfinished work, completed by another’s hand, could achieve such profound and lasting impact. It speaks volumes about the raw power of his initial ideas, the undeniable force of his musical vision.

—

Structure and Soundscape: A Journey Through Grief and Hope

Now, let’s talk about the music itself. Forget the drama of its creation for a moment and just immerse yourself in the sound. The Requiem is scored for four soloists (soprano, alto, tenor, bass), a four-part choir, and an orchestra consisting of two basset horns, two bassoons, two trumpets, three trombones (alto, tenor, bass), timpani, and strings (violins, violas, cellos, double basses).

The choice of instrumentation is telling. The basset horns, with their mellow, slightly melancholic tone, lend a unique color to the work, adding to its somber atmosphere. The three trombones, often associated with sacred music and conveying a sense of solemnity and gravity, are used with chilling effect, especially in the “Tuba Mirum.”

The Requiem Mass follows a traditional structure, but Mozart infuses each movement with his unparalleled dramatic flair and emotional depth. Let’s walk through some of the highlights:

I. Introitus: Requiem aeternam

The work opens with hushed, almost mournful strings, a profound sense of lamentation. The choir enters softly, pleading for eternal rest. It’s a solemn, dignified beginning, setting the tone for the journey ahead. The Kyrie, a double fugue, bursts forth with intricate counterpoint, showcasing Mozart’s mastery of compositional technique even in his final days. It’s a powerful testament to his enduring brilliance.

II. Sequentia: Dies Irae

Ah, the “Dies Irae” (Day of Wrath). This is where things get truly dramatic. The opening is absolutely electrifying, a terrifying orchestral outburst punctuated by the chorus proclaiming the day of judgment. If you’ve never heard it, prepare to be shaken. It’s pure cinematic tension, centuries before cinema even existed.

This movement alone demonstrates Mozart’s incredible ability to paint vivid emotional landscapes with sound. You can almost feel the earth trembling, the heavens opening, and the souls of the dead rising to face their fate. It’s truly breathtaking and, frankly, a little scary.

III. Tuba Mirum

This movement features the four soloists and is famous for its trombone solo, representing the trumpet of judgment. Each soloist gets a moment to shine, lamenting their fate. The trombone solo here is iconic, a haunting, resonant call that sends shivers down your spine. It’s incredibly evocative and perfectly sets the stage for the individual pleas that follow.

IV. Rex Tremendae

A powerful, awe-inspiring chorus where the choir invokes the “King of awful majesty.” It’s full of dynamic contrasts, from hushed pleas to thunderous pronouncements. The sheer weight of the chorus in this section is incredible. You feel the full force of their supplication, a collective cry for mercy.

V. Recordare

A beautifully lyrical and introspective quartet for the soloists. It’s a moment of tender reflection amidst the preceding drama. This is one of my favorite parts – it’s just so exquisitely beautiful and offers a moment of respite, a chance to ponder the individual’s journey.

VI. Confutatis

This movement presents a stark contrast between the fiery pronouncements of the male voices (condemning the damned) and the pleading, softer responses of the female voices (begging for salvation). It’s a dramatic dialogue, a musical representation of the struggle between damnation and redemption. It’s a stark reminder of the choices we face, even in the afterlife.

VII. Lacrimosa

Ah, the “Lacrimosa.” As mentioned, only the first eight measures are Mozart’s. But oh, what eight measures they are! Heartbreakingly beautiful, filled with profound sorrow, leading into Süssmayr’s continuation, which, while not Mozart, manages to maintain the emotional intensity. This is where the unfinished nature of the work truly hits home. It’s a poignant whisper of what might have been.

VIII. Offertorium: Domine Jesu & Hostias

These movements feature more intricate choral writing and soloists, continuing the themes of prayer and offering. The “Domine Jesu” is particularly noteworthy for its dramatic scope and the “Hostias” for its more contemplative, prayerful nature.

IX. Sanctus

This is one of the movements entirely composed by Süssmayr. It’s a more joyful and triumphant section, a declaration of holiness. While it’s Süssmayr’s work, it blends surprisingly well with the overall fabric, perhaps due to his deep familiarity with Mozart’s style.

X. Benedictus

Another Süssmayr composition, often featuring a beautiful quartet for the soloists. It’s a serene and hopeful movement, offering a sense of peace after the drama of the “Dies Irae” and its related sections.

XI. Agnus Dei

Süssmayr’s final original contribution, leading into the “Lux Aeterna” and “Cum sanctis tuis,” which brilliantly reprise the opening themes from the Introit and Kyrie. This cyclical return provides a powerful sense of closure, a final echo of Mozart’s original genius.

The entire work is a masterful balance of powerful choral moments, tender solo passages, and dynamic orchestral writing. It moves from terrifying pronouncements of judgment to moments of profound solace and hope. It’s a journey, not just through the traditional Requiem text, but through the emotional landscape of grief, remembrance, and ultimate peace.

And that, my friends, is why this piece isn’t just a collection of notes. It’s a narrative, a drama, a deeply human expression of the universal experience of loss and the longing for eternity. It truly is a remarkable achievement, a testament to the power of music to articulate the inarticulable.

—

The Legacy That Endures: Why K. 626 Still Resonates

Centuries have passed since Mozart laid down his quill for the last time, yet the Requiem in D Minor, K. 626, continues to exert an almost hypnotic pull on audiences and musicians alike. Why is that? What makes this unfinished, partially completed work so enduringly powerful?

For starters, there’s the sheer quality of Mozart’s original material. Even in its fragmented state, his genius shines through with blinding clarity. The melodic invention, the harmonic richness, the contrapuntal mastery—it’s all undeniably Mozart, at the height of his powers. Even when you know which parts were completed by Süssmayr, the pervasive style and emotional impact remain firmly rooted in Mozart’s vision.

Then there’s the emotional range. This isn’t just a sad piece. It’s a work that encompasses fear, terror, pleading, hope, reverence, and profound sorrow. It takes you on a complete emotional rollercoaster, leaving you breathless and perhaps a little teary-eyed by the end. It touches on universal human experiences: grief, mortality, faith, and the search for meaning in the face of death. This universality is key to its lasting appeal.

Consider the “Dies Irae.” It’s not just a loud chorus; it’s the sound of existential dread, a visceral musical representation of a concept that has haunted humanity since time immemorial. Or the “Lacrimosa,” a moment of such tender, aching beauty that it feels like a collective sigh for all the world’s sorrows. These moments resonate because they tap into something deeply human within all of us.

The mystery surrounding its creation also plays a huge role. The anonymous commissioner, Mozart’s failing health, his belief that he was writing his own Requiem—it all adds to an irresistible narrative. This isn’t just a piece of music; it’s a dramatic story, a legend woven into the very fabric of classical music history. It’s the kind of story that keeps us coming back, pondering the “what ifs” and marveling at the sheer tenacity of a dying genius.

Furthermore, the Requiem has found its way into popular culture, extending its reach far beyond the concert hall. From films like “Amadeus” (which, while dramatized, certainly cemented the legend of the Requiem in the public imagination) to countless documentaries and even video games, its themes and melodies are instantly recognizable. This exposure helps to keep it alive and introduce it to new generations, ensuring its continued relevance.

And finally, it’s a work that demands repeat listening. Each time you hear it, you discover something new. A subtle harmony you missed before, a nuanced phrase from a soloist, a perfectly placed orchestral color. It’s a piece that unfolds slowly, revealing its secrets over time, much like a complex character in a beloved book. It rewards your attention and repays your investment with ever-deeper layers of beauty and meaning.

So, the Requiem endures not just because it’s beautiful, but because it’s profoundly human. It’s a testament to the power of art to grapple with the biggest questions of life and death, to express the inexpressible, and to leave an indelible mark on the soul. It truly is one of the most affecting and important works in the entire classical canon.

—

Experiencing The Requiem: A Listener’s Guide

If you’re new to the Requiem or looking to deepen your appreciation, here are a few tips and recommendations. Trust me, it’s worth the investment of your time.

Choosing a Recording

This is where it gets fun, and a little overwhelming, because there are literally hundreds of recordings of the Requiem out there. Everyone has their favorites, and opinions vary wildly. But here are a few highly regarded ones to get you started:

- Karl Böhm with the Vienna Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon): A classic, traditional interpretation. Big, lush, and deeply moving. This is often a go-to for many classical music lovers.

- Sir Colin Davis with the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO Live): A powerful and dramatic reading, often praised for its intensity and superb choral work.

- John Eliot Gardiner with the English Baroque Soloists (Archiv Produktion): If you’re interested in historically informed performance (HIP), this is a brilliant choice. It offers a leaner, more agile sound, closer to what Mozart would have heard.

- Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon): Grand, sweeping, and undeniably epic. A very dramatic interpretation, showcasing the power of a large modern orchestra.

- Richard Maunder’s completion: While most recordings use Süssmayr’s version, seek out recordings that use Maunder’s completion for a fascinating alternative perspective. Robert Levin’s completion is also gaining popularity for its scholarly approach.

My advice? Listen to clips of a few different versions online. See what resonates with you. Some prefer the grandeur of a large modern orchestra; others lean towards the crispness and historical accuracy of period instruments. There’s no wrong answer here; it’s all about what moves you.

Attending a Live Performance

If you ever have the opportunity to hear the Requiem performed live, seize it! There is simply no substitute for experiencing the raw power of a full choir and orchestra in a concert hall. The vibrations, the acoustics, the shared experience with hundreds of other listeners – it’s transformative. Keep an eye on local symphony orchestra schedules, church choirs (especially around Easter or All Saints’ Day), and university music departments.

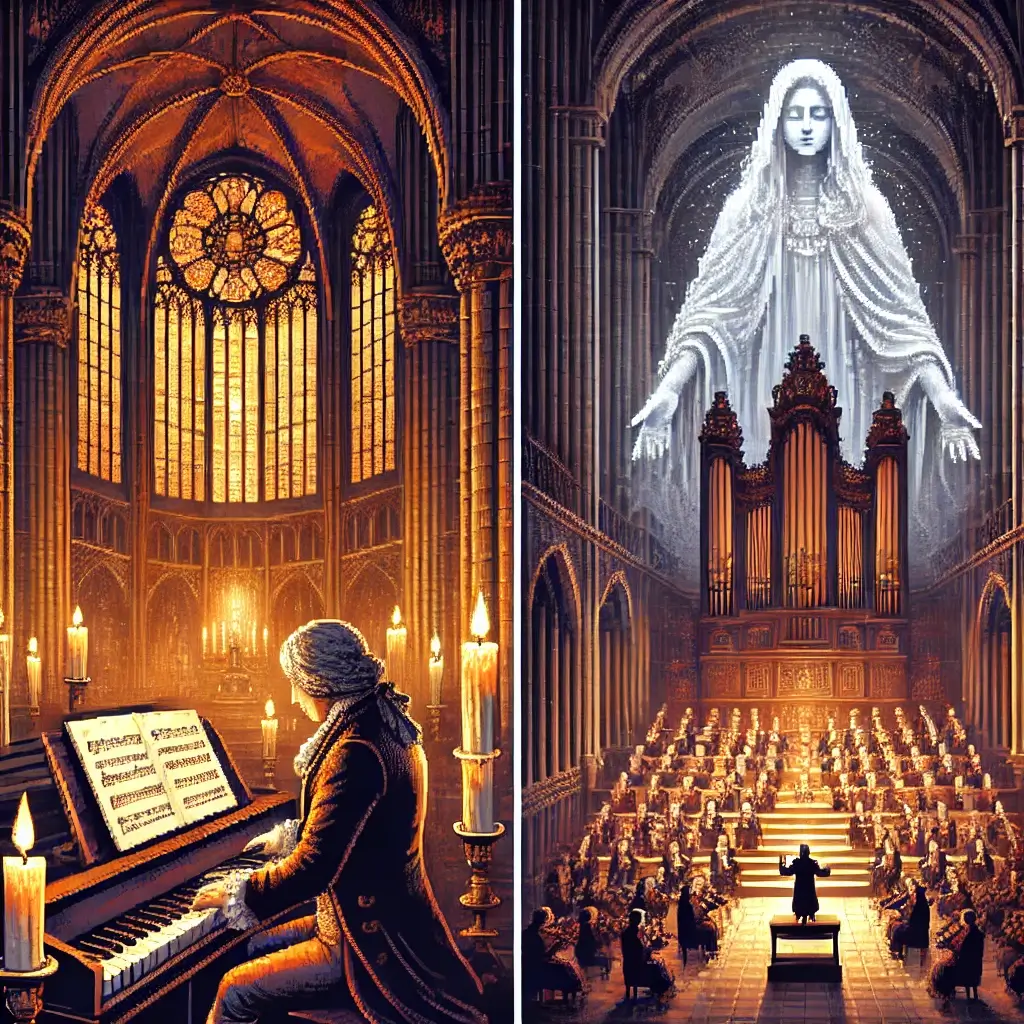

I remember attending a performance of the Requiem in an old cathedral once. The stone walls, the stained glass, the way the sound reverberated – it was almost spiritual. It felt like the music was truly designed for that space, enveloping every single person in the audience. It’s a memory I’ll cherish forever.

What to Listen For

When you listen, pay attention to the contrasts: the terrifying outbursts of the “Dies Irae” contrasted with the sublime beauty of the “Recordare.” Notice how Mozart (and Süssmayr) uses the different sections of the choir – basses, tenors, altos, sopranos – to create dialogue and emotional tension. Listen for the distinct colors of the instruments, especially the basset horns and trombones, and how they contribute to the overall mood.

Don’t be afraid to let the music wash over you. You don’t need to analyze every note to appreciate its power. Just open yourself to the emotions it evokes. It might make you feel sad, or reflective, or even a little bit hopeful. Whatever it is, embrace it. That’s the magic of this piece.

—

Beyond the Notes: Personal Reflections on K. 626

Having immersed myself in the world of Mozart’s Requiem for so long, it’s become more than just a piece of music to me. It’s a reminder of human fragility, artistic perseverance, and the enduring power of creation in the face of inevitable end.

There’s a humility that comes with listening to the Requiem. It forces you to confront your own mortality, not in a morbid way, but in a reflective, almost comforting sense. It reminds us that even the greatest among us are subject to the same universal laws, the same inevitable journey. And yet, through their art, they leave something behind that transcends their physical presence.

I often find myself thinking about Mozart, a brilliant young man, battling illness, yet pouring every ounce of his remaining energy into this work. It’s a testament to the human spirit’s capacity for creativity even under the direst circumstances. It makes me wonder what unfinished projects we all leave behind, and what quiet, unacknowledged acts of completion happen after we’re gone.

The Requiem is also a powerful metaphor for life itself. It has moments of intense joy and profound sorrow, periods of chaos and moments of serene peace. It’s never one thing for very long, much like our own experiences. And just as Süssmayr completed the Requiem, we often rely on others to help us finish our own life’s work, to carry on our legacy, to tell our story when we no longer can.

So, the next time you hear a snippet of the Requiem, or decide to listen to the whole thing, take a moment. Don’t just hear the notes; feel the history, the human drama, the whisper of a dying genius leaving behind his most profound and haunting farewell. It’s a piece that truly lives and breathes, and it will stay with you long after the final chord fades.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I think I’m going to put on the “Dies Irae” again. Sometimes, you just need a good musical shake-up to remind you of the incredible power of art. And K. 626 delivers, every single time.

—

Further Exploration & Resources

Ready to dive deeper into the world of Mozart and his Requiem? Here are some trusted external links where you can find more information, listen to performances, and explore the history.

Explore Mozart’s Birthplace (Mozarteum) Mozart Biography (Britannica) London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) – Learn about their history and recordings

Mozart, Requiem, K. 626, Classical Music, Unfinished Masterpiece